How the Brown Act protects you from “Your Secret Government”

- By : Michael Baldwin

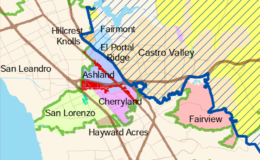

- Category : Alameda County, CVSAN, CVUSD, EBMUD, Fairview Fire Protection District, Governance, HARD, MAC, State of California

If you’ve ever attended a meeting of any local agency, you may have heard of the Brown Act, but do you know what it is, and what it is for? It has nothing to do with Jerry Brown or UPS, but it has everything to do with keeping meetings and the decision-making process open for all citizens to see. Unfortunately, the Brown Act also often has the unintended (and unnecessary) consequence of paralyzing public bodies when engaging the public.

The Ralph M. Brown Act (named for the bill’s author) was passed by the California Legislature in 1953. The Act was spurred by many examples of “back room deals,” and many reported instances of the public being kicked out of public meetings because the public body did not want public observation of their business. A ten part series in the San Francisco Chronicle in 1952 titled “Your Secret Government” exposed the problems for all to see, and State Senator Ralph Brown of Modesto created this law which passed with no real opposition. It guaranteed the public’s right to attend and participate in meetings of local boards, councils and commissions. The act states its purpose as:

The Ralph M. Brown Act (named for the bill’s author) was passed by the California Legislature in 1953. The Act was spurred by many examples of “back room deals,” and many reported instances of the public being kicked out of public meetings because the public body did not want public observation of their business. A ten part series in the San Francisco Chronicle in 1952 titled “Your Secret Government” exposed the problems for all to see, and State Senator Ralph Brown of Modesto created this law which passed with no real opposition. It guaranteed the public’s right to attend and participate in meetings of local boards, councils and commissions. The act states its purpose as:

In enacting this chapter, the Legislature finds and declares that the public commissions, boards and councils and the other public agencies in this State exist to aid in the conduct of the people’s business. It is the intent of the law that their actions be taken openly and that their deliberations be conducted openly. The people of this State do not yield their sovereignty to the agencies which serve them. The people, in delegating authority, do not give their public servants the right to decide what is good for the people to know and what is not good for them to know. The people insist on remaining informed so that they may retain control over the instruments they have created”

The act applies to the “legislative bodies” of all local agencies in California and includes most councils, boards, commissions and committees. The primary rules of the Brown Act are:

- Post public notices of all regular meetings at least 72 hours in advance

- Limit action to those items listed on the agenda

- Hold meetings in the jurisdiction of the agency

- Not require a “sign in” for anyone

- Allow recording and broadcast of the meetings

- Allow the public to address the council

- Conduct only public votes, with no secret ballots

- Treat documents as public “without delay”

- Closed meetings may be held in specific circumstances, including Personnel and Litigation issues

That’s pretty much it. Simple stuff, right? The basic problem is that over the years a number of Brown Act “traps” have been uncovered/alluded to which confuse the heck out of many local officials. Let’s take them one at a time.

The “Serial Meeting” trap: “It’s not really a meeting unless we’re all in the same place at the same time, right?”

The “serial meeting” is defined by the code as:

A “serial meeting” is a series of communications through direct communication, writings, personal intermediaries, e-mail or other technological devices to develop a “collective concurrence” as to a proposed action or decision. (§ 54952.2 (b).)”

Think of this as a big game of “telephone.” The chair of a body calls or emails another member to decide how to proceed on a certain issue. That second member calls/emails a third member to further discuss, and so on. This amounts to the body deliberating in private, out of the public view.

By the time the matter is before the public at an open meeting the decision has been made. That’s a Brown Act no-no, but many bodies have overreacted to this and prohibited members from even replying to incoming emails from constituents and staff on topics which may/may not come before the body in the future. Many bodies have also extended this to Facebook and other social media.

By the time the matter is before the public at an open meeting the decision has been made. That’s a Brown Act no-no, but many bodies have overreacted to this and prohibited members from even replying to incoming emails from constituents and staff on topics which may/may not come before the body in the future. Many bodies have also extended this to Facebook and other social media.

Here is what the law actually means:

- Members may receive one-way communications from members of the public and from staff, including e-mail (and by extension social media), on agenda matters

- As a general rule, two-way communications between members, including replies to e-mail, give rise to “serial meeting” questions

- Board staff may communicate separately with board members regarding a matter if staff does not communicate to members the comments or position of any other member of the board

So, members can politely reply to inquiries via electronic means, but they should refrain from extended replies to the public on such matters that are on the agenda and refer them to the next public meeting about the topic instead.

The “Public Meeting” trap

“The Board has been invited to a Holiday party. We have to make sure less than a quorum attends, or it will be considered a public meeting and none of us can interact with anyone!!”

This absurd sounding idea is actually taken very seriously by many bodies, even if it’s not true. As the law states:

The following actions and activities do not constitute “meetings” as long as the members do not discuss the body’s business among themselves:

- Individual contacts with non-agency members

- Attendance at community meetings

- Attendance at meetings of other local bodies

- Attendance at social gatherings

- Attendance at meetings of standing committees

- Attendance at public conferences

So, members of a body may attend anything they want like a conference or a retirement party, but members can’t discuss business among themselves that is pending before the body.

Pretty straightforward.

The “Not on the Agenda” trap

“A member of the public asked a question during the meeting. We can’t say ANYTHING about it since it’s not on the agenda!!”

This one has a grain of truth, but many bodies interpret it in a much more draconian way.

The law states:

Items not on the agenda may not be discussed unless they relate to:

- A response to a statement made by a member of the public exercising his or her public testimony rights

- An emergency situation

- Brief questions, announcements or reports on a member’s activities

- A purely procedural matter

If Joe Q. Public stands up during public comment and says “what the heck is going on with…” the body can give a basic reply, but in-depth responses and discussion should be withheld until the item can be put on a future agenda. This lets the rest of the public know that a certain item will be discussed. Many bodies overreact and simply respond to a “what the heck is going on with…” inquiry with a “Thank you. Next!” reply out of unnecessary wariness.

The public may also address the body on matters of general interest, but the agency may not take official action on any item raised by the public at the same meeting at which it was raised.

The public may also address the body on matters of general interest, but the agency may not take official action on any item raised by the public at the same meeting at which it was raised.

In the 62 years since the Brown Act was adopted, there has never been a prosecution of its violation. If there were, the offender would be charged with a misdemeanor punishable by a $1,000 fine.